Incentives to Migrate Improve Food Security

Organization : Innovations for Poverty Action

Project Overview

Project Summary

Microcredit organizations in Bangladesh gave households a small financial incentive to send someone to a nearby urban center to look for work during the lean season.

Impact

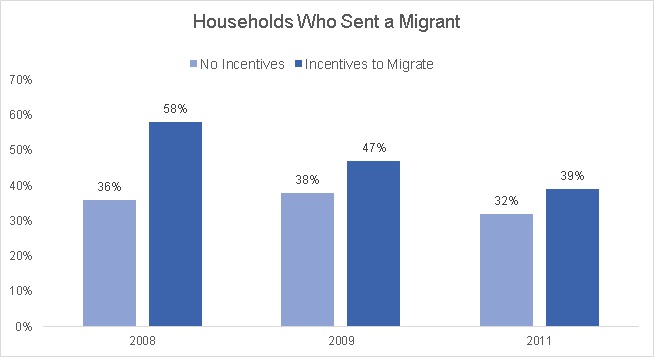

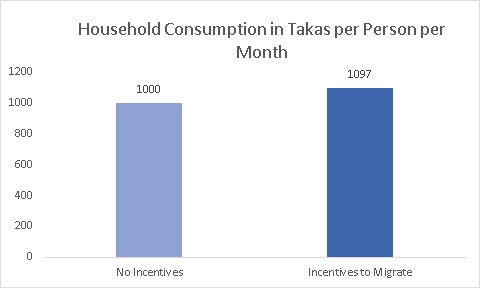

The incentive increased the likelihood of migration by 22 percentage points in the first year, with small long-term effects up to two years later. Families that were offered incentives also ate better during the hungry season.

Cost

The cost was $11.50 per incentive, plus personnel costs. Researchers estimate that every dollar invested generated between $2 and $6 in benefits, in terms of increased consumption and income for beneficiary households.

Challenge

Three hundred million of the world’s rural poor suffer from seasonal hunger, which often occurs between planting and harvest when the demand for agricultural labor falls.[1] In the Rangpur region of Bangladesh, high levels of poverty and seasonal famine make seasonal migration from rural to urban areas a potentially advantageous strategy for increasing income and improving food security, but few people actually migrate.

The fact that some people choose to stay behind and risk famine indicates that there may be barriers to migration, such as financial constraints, lack of information about urban job opportunities, or a desire to remain with family. A Bangladeshi microfinance institution partnered with researchers to see if a small incentive to migrate would be sufficient to overcome the barriers to migration.

Design

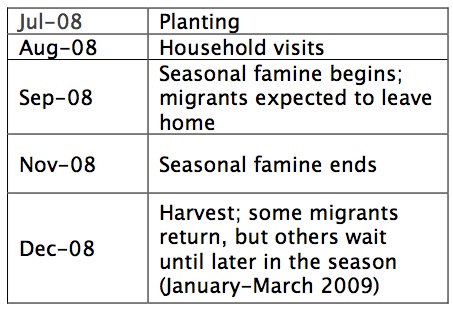

Timeline: household visits were conduted after the planting season

The Palli Karma Sahayak Foundation coordinated a program that offered small incentives to encourage people to migrate for work during the lean season. Representatives from RDRS offered households in the Rangpur region 600 takas (around $8.50) on the condition that they would send a member of their household to a nearby city during the lean season to work. The representatives also provided information about the experience of migration: the types of jobs available in urban locations, the likelihood of getting each job, and approximate wages.

Excerpt from an actual script

We would like to give you information on job availability, types of jobs available, and approximate wages in four regions—Bogra, Dhaka, Munshigonj, and Tangail

…

Three most commonly available jobs in Dhaka are: (a) rickshaw-pulling, (b) construction work, (c) day labor. The average wage rates per day are Tk. 250 to 300 for rickshaw-pulling, Tk. 200 to 250 for construction work, and Tk. 150 to 200 for day laborer. The likelihood of getting such a job in Dhaka is high

…

Based on the above information, would you/any member of your family like to go to any of the above locations during this monga season? If so, where do you want to go? Note that the job market information given above might have changed or may change in the near future and there is no guarantee that you will find a job….

Migrants collected an additional 200 takas (around $3.00) when they reported to the microfinance organization at their migration destination. Incentives were given either in the form of cash or a zero-interest loan.

Impact

A randomized evaluation found that the incentive greatly increased the likelihood of migration, and families that were offered the incentives ate better during the hungry season. Families that were offered an incentive were also more likely to send a migrant in later years—even without receiving any additional incentives. Researchers estimate that every dollar invested in the seasonal migration program in Bangladesh generated between $2 and $6 in benefits, in terms of increased consumption and income for beneficiary households.

A randomized evaluation found that the incentive greatly increased the likelihood of migration, and families that were offered the incentives ate better during the hungry season. Families that were offered an incentive were also more likely to send a migrant in later years—even without receiving any additional incentives. Researchers estimate that every dollar invested in the seasonal migration program in Bangladesh generated between $2 and $6 in benefits, in terms of increased consumption and income for beneficiary households.

What worked best?

- Small incentives that covered one round trip between the migrants’ origin and destination. Researchers believe that the incentive needs to mitigate the risks that migrants feel they take by spending the money to travel to a new place to look for work.

- Framing the incentives as conditional on migration, meant to defray the cost of travel. Further research suggested that making the cash/credit an incentive conditional on migration—rather than as an unconditional grant or loan—was important.

- The households that were mostly like to send a migrant were very poor, living on around 1,500 calories per day, and spent almost all their money on food. Targeting programs to these households may be most effective.

What didn’t work?

- Providing information about migration without also giving a financial incentive did not encourage migration.

- Giving migrants additional restrictions (e.g., specifying where they needed to migrate to) decreased the effectiveness of the incentives.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researcher:

Would this work elsewhere?

While this approach has only been tested in Rangpur, Bangladesh, multiple rounds of research in Rangpur indicate that small incentives can motivate people to migrate, leading them to find work and improve their food security. Researchers believe that these results may be generalizable to other contexts where the same conditions apply:

- Where rural households face hunger, famine, and unemployment between planting and harvesting on a regular basis;

- Where labor markets in urban centers are hospitable to seasonal migrants, urban centers are reachable, travel costs are low, and travel is relatively safe;

- Where migrants have access to a method for transmitting remittances during their migration, or are able to save for more than one trip during the season.

Advice for implementers

- As in many interventions, establishing strong rapport with local leaders in villages is crucial. Some leaders were initially confused about the intentions of the NGOs, and conflated encouraging people to migrate with human trafficking. NGOs worked with community leaders (many of whom already had strong relationships with NGO representatives) to overcome this confusion and gain their support.

Cost effectiveness

An incentive covering a migrant’s travel cost is less expensive than other strategies to combat seasonal famine, such as seasonal microcredit and feeding programs, especially because incentivizing people to migrate in one year can motivate them to migrate again in subsequent years, whereas feeding and credit programs must be offered year after year. Costs you are likely to encounter include:

- Cost per incentive (grants are more expensive than loans, since some proportion of the loans will be paid back to the lender)

- Personnel time for visiting households and distributing incentives, at places of origin and at migration destinations.

Scripts for informing families about migration

In the original evaluation, potential migrants were provided with information on the types of jobs available in each of four urban areas: Bogra, Dhaka, Munshigonj, and Tangail. In addition, they were told the likelihood of finding such a job, and the average daily wage in each job. This information was provided using the following script:

“We would like to give you information on job availability, types of jobs available, and approximate wages in four regions—Bogra, Dhaka, Munshigonj, and Tangail. They are not in any particular order. NGOs working in those areas collected this information at the beginning of this month.

Three most commonly available jobs in Bogra are: (a) rickshaw-pulling, (b) construction work, (c) agricultural labor. The average wage rates per day are Tk. 150 to 200 for rickshaw-pulling, Tk. 120 to 150 for construction work, and Tk. 80 to 100 for agricultural laborer. The likelihood of getting such a job in Bogra is medium (not high/not low).

Three most commonly available jobs in Dhaka are: (a) rickshaw-pulling, (b) construction work, (c) day labor. The average wage rates per day are Tk. 250 to 300 for rickshaw-pulling, Tk. 200 to 250 for construction work, and Tk. 150 to 200 for day laborer. The likelihood of getting such a job in Dhaka is high.

Three most commonly available jobs in Munshigonj are: (a) rickshaw-pulling, (b) land preparation for potato cultivation, (c) agricultural laborer. The average wage rates per day are Tk. 150 to 200 for rickshaw-pulling, Tk. 150 to 160 for land preparation, and Tk. 150 to 160 for agricultural laborer. The likelihood of getting such a job in Munshigonj is high.

Three most commonly available jobs in Tangail are: (a) rickshaw-pulling, (b) construction work, (c) day laborer in brick fields. The average wage rates per day are Tk. 200 to 250 for rickshaw-pulling, Tk. 160 to 180 for construction work, and Tk. 150 to 200 for brick field work. The likelihood of getting such a job in Tangail is medium (not high/not low).”

Do you accept the offer? I will come back in a week’s time. Note that the job market information given above might have changed or may change in the near future and there is no guarantee that you will find a job, and we’re just providing you the best information available to us. Note also that we or the NGOs that collected this information will not provide you with any assistance in finding jobs in the destination.”

About the implementing organizations

Much of the actual implementation was done by partner organizations in the field, most notably RDRS, an NGO operating in the Rangpur region in Bangladesh. Established in 1972 to assist with relief and rehabilitation of greater Rangpur-Dinajpur region immediately following the War of Independence, the RDRS program evolved into a comprehensive effort. Formerly the Bangladesh field program of the Geneva-based Lutheran World Federation/Department for World Service, RDRS became a national development organization in 1997. RDRS is now providing its development support to around 2,000,000 people in 13 districts in Bangladesh.

Palli Karma Sahayak Foundation was responsible for NGO selection and coordination. PKSF is a nonprofit microcredit funding and capacity building organization that was set up by the Government of Bangladesh in 1990. PKSF works with a number of partner NGOs in the area of Rangpur where the original program evaluation took place, and helped the researchers select which of these NGOs (including RDRS) would distribute the incentives. These NGOs were already implementing microcredit programs in the 100 villages that took part in the project, and so were well-equipped to disburse the funds to recipients.

Project Credits

Researchers:

Gharad Bryan Contact London School of Economics and Political Science

Shyamal Chowdhury University of Sydney

Mushfiq Mobarak Yale University

[1] Devereux, Hauenstein and Vaitla (2008). Seasons of Hunger: Fighting Cycles of Starvation among the World’s Rural Poor. Pluto Press.