Don’t Blame the Messenger: Delivery Methods for Increasing Tax Compliance

Organization : Inter-American Development Bank

Project Overview

Project Summary

More than 20,000 taxpayers with due liabilities were randomly assigned to receive a message from the Colombian National Tax Agency regarding payments due through one of three delivery mechanisms (letter, email, or personal visit by a tax inspector), or not at all.

Impact

Results indicate large and highly significant effects, as well as sizable differences across delivery methods. A personal visit by a tax inspector is more effective than a physical letter or an email, conditional on delivery, but email tends to reach its target more often.

Cost

$0 per email, $0.50 per letter, and $8 per personal visit, as estimated by the tax agency.

Challenge

There is growing interest in explaining what motivates individuals to pay their taxes in full and on time, and what is the best way to deal with those who do not declare the total amount of tax or who are behind with their payments. While many studies have evaluated the comparative effect of sending deterrence and moral persuasion messages to taxpayers, this experiment evaluates how the same message, using different delivery methods, can affect tax compliance.

Once every few months, the National Tax Agency of Colombia (DIAN) contacts taxpayers with due liabilities (declared but unpaid taxes) by mail (sometimes making sporadic in-person visits). During one of these National Revenue Collection Days, DIAN agreed to randomize the delivery mechanism of such messages in order to test their comparative efficiency.

Design

Around 21,000 taxpayers due to receive a message from DIAN between September and October 2013 were randomly assigned to one of three different delivery methods (physical letter, e-mail, or inspector visit) or to a control group, which did not receive any message.

The message included in both the physical letter and the email was exactly the same. It stated the account balance, the type of tax, and the year or month it had not been paid, as well as information on methods of payment and the cost that the taxpayer was incurring by not paying (interest and penalties, potential legal action, and possible effect on credit history). Finally, it provided a moral suasion message (“Colombia, a commitment we can’t evade”). The message concluded with the contact information of a tax agency authority.

Personal visits had a unique protocol that inspectors were supposed to follow at the time of the visit if the taxpayer was present at the physical address (another protocol was implemented in the case of absence), which followed the same logic as the written messages: the taxpayer was informed about his or her standing tax delinquencies and urged to pay. Inspectors were supposed to mention the penalties the taxpayer was incurring and the possibility of further legal actions in case of noncompliance. The visit was closed by the verbal delivery of a moral suasion message. Complete contents of emails, letters and visit protocols are included (in Spanish in Appendix B of the referenced paper).

Impact

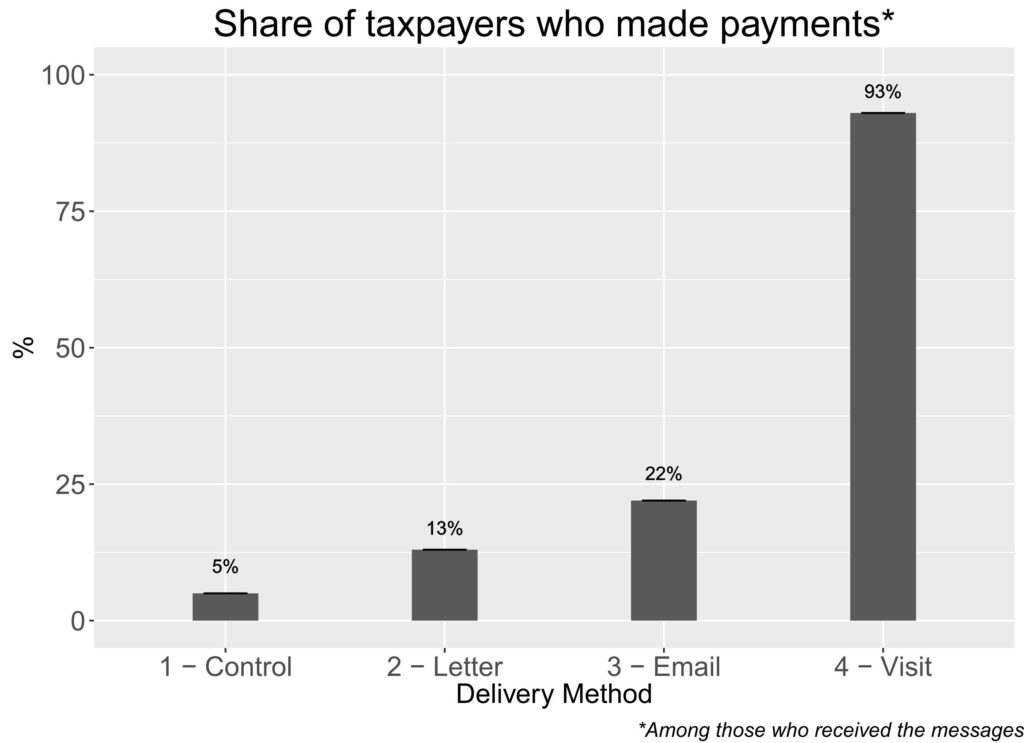

Among those assigned to a letter (intent-to-treat results) the probability of making any payment towards their debt was 4 percentage points higher than receiving no message (control group). Given that the underlying probability of making payments for the control group is about 5 percent, sending a letter almost doubles the probability that the taxpayer would pay down their debt. The other two delivery methods, email and personal visits, have an even larger impact on making a payment: about 14 percentage points higher than no message (three times higher impact.)

Among those who actually received the messages, payment of outstanding debt was much higher: about 8 percentage points higher than the control group for those receiving a letter, 17 percentage points higher for those receiving an email, and about 88 points higher for those receiving a personal visit. That is, almost every person who received a visit by a tax inspector made some kind of payment.

The average amount collected was around US$590 per email, US$550 per letter, and over US$2,000 for attempted in-person visits. Moreover, we found large spillover effects, with those receiving messages making payments of other due taxes too.

All 3 delivery methods produced significantly higher (p<0.05) payment rates compared to the control group.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researchers:

- Taxpayers with relatively low debts (US$20 PPP) or high debts (US$46,000 PPP) were excluded. The randomization was made in six blocks according to the size of the debt and whether the debt was recent or not.

- Because of issues of one-sided noncompliance with the assignment to the treatment (for example, some people did not receive the messages because their address was incorrect or because the agency could not get to them within the frame of the exercise), both ITT (intent-to-treat) and TOT/LATE (treatment-on-the-treated/local average treatment effect) effects were estimated. Approximately half of the taxpayers could not be located (this average varies significantly by treatment, from 75 percent for the personal visits to 12 percent for the email).

Project Credits

Researchers:

Daniel Ortega Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and Instituto de Estudios Superiores de Administración (IESA)

Carlos Scartascini Inter-American Development Bank