Increasing Voter Turnout in Tunisian Elections

Organization : Democracy International

Project Overview

Project Summary

Eligible voters in Tunisia received leaflets encouraging them to vote using either planning prompts, social pressure, gratitude, or sarcasm. Leaflet distribution teams either left leaflets at the door or delivered them personally during door-to-door canvassing.

Impact

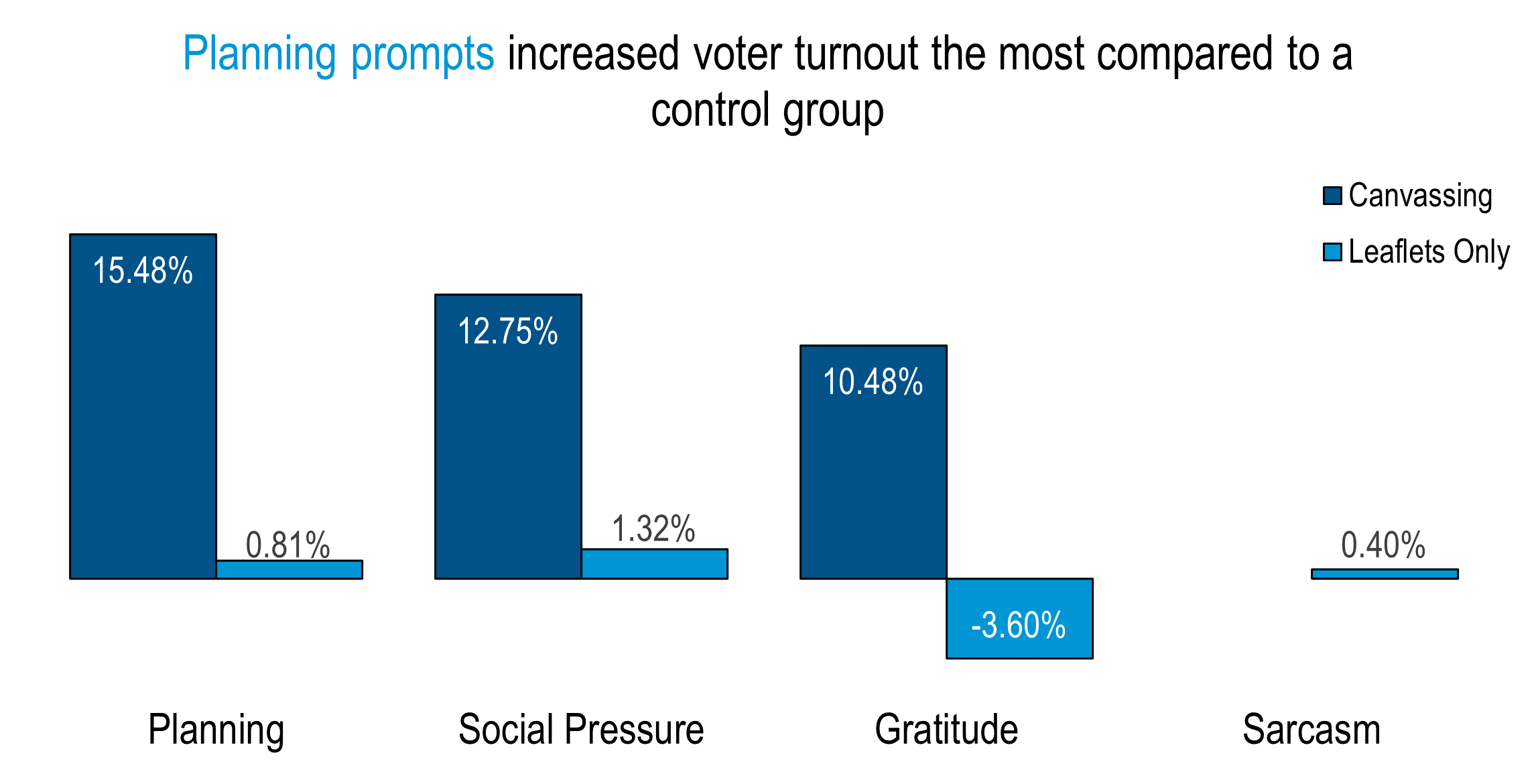

Encouraging voters to make a voting plan via canvassing was most effective, increasing voter turnout in municipal elections by 15.5% compared to a control group—from 39.6% to 55.5%, adjusting for known drivers of turnout.

Source

Source

Challenge

How can new democracies sustain an active citizenry that believes in fundamental democratic principles and participates in the democratic process? Although Tunisia remains the only democratic transition from the Arab Spring, its citizens are growing disillusioned with democracy. The proportion of Tunisians who prefer democracy over all other political systems plummeted 25 percent between 2013 and 2018 according to Afrobarometer data, and voter turnout has decreased with each election cycle.

Many Tunisians—especially young Tunisians, who make up close to 40 percent of the population—express disillusionment with elections. This is not uncommon in new democracies. Following regime change, intrinsic support for democracy as an end in itself can give way to conditional support based on improvements in material living standards and other “instrumental” evaluation criteria [1]. In the extreme, however, elected governments that fail to meet citizen expectations can lose legitimacy not only for democratic elections, but also for electoral democracy as a system of government. In such contexts, electoral democracy may benefit from a “booster shot” in the form of voter mobilization.

Design

Eligible voters received a two-sided leaflet as part of a Get Out the Vote (GOTV) voter mobilization campaign. One side showed the Tunisian flag, a ballot box, a number to text for registration information, and the election date. The other side showed one of four encouragements to vote (see Figure 1). The four potential encouragements to vote (delivered in Arabic) were:

1) Planning: “Do you have a plan for Sunday, May 6?” with prompts to articulate when they will vote, how they will get to the polling place, with whom they will go, and what they will do after they vote.

2) Social Pressure: “Did you know that some neighborhoods vote more than others? Don’t let your neighborhood vote less than others.”

3) Gratitude: “Thank you for having an interest in the destiny of your region by participating in the municipal elections.”

4) Sarcasm (delivered only via leaflet, not in-person canvassing): “If you are satisfied with the situation of the country, don’t vote.”

Distribution teams either left leaflets at the door or delivered them personally through door-to-door canvassing during a large campaign one to two weeks prior to the election. Canvassers followed a script to remind voters about the election and deliver the assigned message.

Democracy International (DI), with funding from the U.S. Department of State, randomly allocated these interventions to 1,750 polling center “catchment areas” and assigned 400 polling centers to a “pure control” condition (i.e. no message at all).

Impact

A randomized evaluation found that, overall, canvassing was more effective than leafleting alone. Canvassing generated 10.5 percent greater turnout than leafleting. Leafleting alone was generally weak and ineffective—groups who received leaflets alone did not differ statistically from control groups who did not receive any GOTV messaging or, in the case of gratitude messages, had statistically lower turnout.

Voters who received a canvassing message of planning, social pressure, or gratitude were significantly more likely to vote than voters who received no message at all by 15.5%, 12.8%, and 10.5% respectively (p < .05). Turnout from the social pressure message did not significantly differ from turnout in the planning or gratitude message groups. However, gratitude messages were significantly less effective than planning messages (p < .05).

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researchers:

- It is important to customize messaging campaigns to the context and target audience. Typical GOTV social pressure campaigns shame voters for previously failing to vote and/or promise to monitor future turnout. In post-authoritarian contexts, including Tunisia, these tactics could undermine trust in ballot secrecy or recall surveillance by secret police. We adapted our social pressure message to prompt neighborhood comparisons, at the suggestion of focus group discussants.

- To ensure our campaign was culturally appropriate and would not cause harm, DI:

- Finalized flyers following focus group consultations;

- Consulted a scholar of sociology to evaluate messages for cultural appropriateness and potential psychological harm; and

- Commissioned a political marketing specialist to review color scheme, graphics, and general presentation to ensure no flyer appeared unintentionally partisan.

- For experimental design, it is critical to design for informational spillover using block-randomization within geographic clusters. In villages, a canvasser would likely need to discuss what they are doing with onlookers when delivering a message at one house. And it is almost guaranteed people will talk to one another. We suggest drawing out a radius using a community landmark (e.g., mosque, café) as an epicenter assuming people within that radius will communicate about the intervention.

Project Credits

Researchers:

Aaron Abbarno Democracy International

Laura Van Berkel Democracy International