Labeled Cash Boosts School Attendance

Organization : Innovations for Poverty Action

Project Overview

Project Summary

A small cash payment was paid out to families of school-aged children, not conditional on school attendance but explicitly labeled as an education support program.

Impact

There was a 7 percentage point increase in school participation (from 74% to 81%) and a 12 percentage point increase in re-entry to school (from 15% to 27%).

Cost

On average, this program costs $99 per child per year ($89 in transfers; $10 in administration).

Challenge

Conditional cash transfers are funds given to households if they fulfill certain requirements, such as sending their children to school. These cash transfers can boost households’ investment in health and education; however, they are expensive, and it is often complicated to track and enforce compliance with the requirements. Removing the conditions may make cash transfer programs more cost effective by decreasing administrative costs, while still providing a nudge to increase school participation.

Design

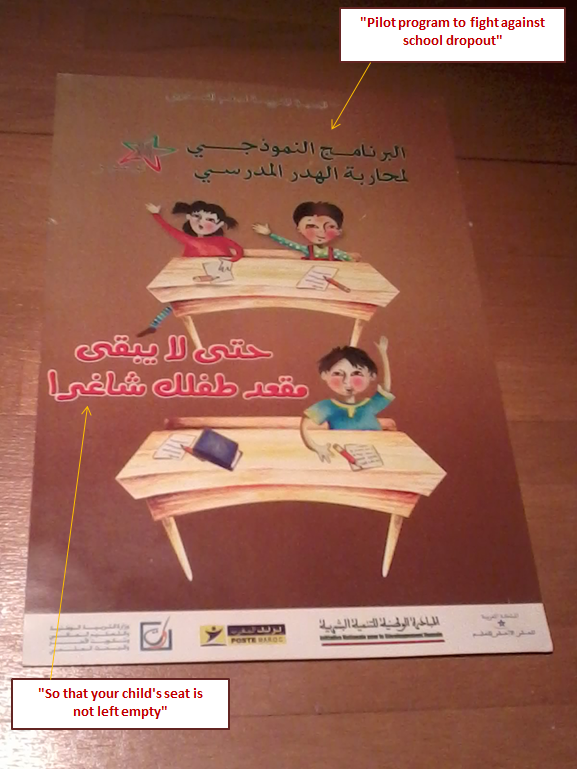

A flyer for the cash transfer program

The Moroccan Ministry of Education piloted a “labeled cash transfer” (LCT) program that made cash payments to parents of children aged 6 to 15 years. The program did not require that participants actually attend school in order to receive the payment, but the program’s features made it very clear that the program was linked to school attendance:

- School headmasters were responsible for enrollment and informing the parents of school-aged children about the program.

- Parents enrolled their children in the program at school.

- Because enrollment happened at school, headmasters also enrolled children in school while signing them up for the program.

- The flyers that schools used to promote the program in communities showed children sitting at their school desks and had the headline “Pilot program to fight against school dropout,” and the phrase “So that your child’s seat is not left empty.”

To reduce both the cost of determining program eligibility as well as any confusion that participants might feel about whether or not they qualified, all children in the participating school districts could enroll in the program.

The payments were much larger than a family’s yearly schooling expenditures, but smaller than most conditional cash transfers. The average payment represented 5 percent of the average monthly household consumption, but the range for most conditional cash transfers is between 6 and 27 percent of mean monthly household consumption.

Recipients received cash transfers at their local post office. About a third of participants, who lived in areas that did not have a post office, received the visit of a “mobile cashier” in charge of distributing the transfers.

Impact

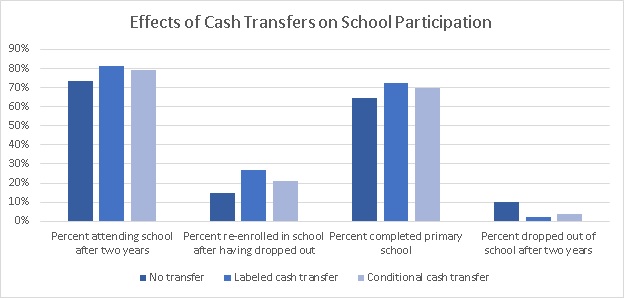

A randomized evaluation found that over two years, the labeled cash transfer (LCT) significantly increased school participation, re-enrollment of school dropouts, and primary school completion. In fact, as indicated by the graph, the labeled cash transfer had larger effects on school participation than the more expensive conditional cash transfer, in which families only received transfers if their child did not miss school more than four times per month.

- School attendance at schools with the LCT program increased by 7 percentage points to 81%, compared to 74% at schools without the program.

- 27% of students at LCT schools who had dropped out prior to the program re-enrolled during the two years of the LCT pilot, a 12 percentage point increase compared to non-LCT schools.

- The program also improved primary school completion by 8 percentage points (72% at LCT schools; 64% at non-LCT schools) and reduced school dropouts by 8 percentage points (10% at LCT schools; 2% at non-LCT schools).

- Interest in the program was very high; 97% of households had at least one child enrolled in the program by the end of the second year.

Perceptions of school quality increased in communities with the cash transfer program, and parental beliefs regarding the returns to education also dramatically increased. The program also reduced the number of students who dropped out because they did not want to be in school as well as the number of students who dropped out because they thought their school was of poor quality. This indicates that the program works by increasing the salience of education for parents, and by serving as a positive signal about the value and quality of education at their local school.

What worked best:

- The labeled cash transfer not only achieved greater impacts on school participation than the conditional cash transfer for less expense, but also avoided complications with implementation caused by tracking and enforcing the conditionality.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researcher:

Would this work elsewhere?

This project was conducted in rural school districts in a middle-income country where school attendance is generally high at early ages, and where two common reasons for dropping out are financial difficulties and children’s lack of interest. Results indicate that small cash transfers without conditions, but with explicit labels tying them to education, can change parental perceptions and improve school retention. Researchers believe that these lessons may be generalizable to other contexts where the same basic conditions apply.

A large body of evidence supports the efficacy of cash transfers as a way to boost households’ investment in health and education.[1] A growing number of researchers and organizations are experimenting with reducing or eliminating the conditionality component of these transfers, and the evidence generally supports the efficacy of unconditional cash transfers.[2]

Advice for implementers

- It is important to be aware of administrative capacity and needs when implementing a program of this size. For example, because many families did not have the government ID cards necessary to register for the program, the government sent mobile registration offices to the area before the program began.

Tools and resources for implementers

- Transfer amount details: The payments increased with age, starting from 60 Moroccan dirhams (MAD) per month (around US$8 in 2008) per child aged 6-7 years to 100 MAD per month (around US$13 in 2008) per child aged 10-11 years.

- Household costs incurred when receiving transfers: Implementers may want to keep in mind the cost that families incur by having to travel to pick up their transfers and find ways to mitigate that cost. In the Morocco LCT program, on average, the cost of a round trip to the nearest pick-up point was around 20 MAD (around US$2) or 8 percent of the average transfer. However, if they wanted to save on transportation costs, recipients could wait and withdraw all their transfers at once.

Cost effectiveness

Labeled cash transfers are generally less expensive per dollar distributed than conditional cash transfers since tracking and enforcing conditionality can be costly. In Morocco, the Ministry of Education spent approximately $10 in administrative costs per child per year to run the LCT program, in addition to an average of $89 per child per year in transfers. As mentioned above, the transfer represented around 5 percent of average household consumption. (The conditional cash transfer cost around $13 per child per year to administer, in addition to an average of $85 per child per year in transfers.)

Costs you are likely to encounter include:

- Costs associated with transferring money to individual recipients

- Staff time and training for disbursing transfers (including travel to any remote locations and any banking fees)

- Staff time and training for enrolling and tracking participants

- Staff time and printing costs for developing and producing promotional materials

Project Credits

Researchers:

Najy Benhassine The World Bank

Florencia Devoto J-PAL; Paris School of Economics

Esther Duflo Massachusetts Institute of Technology; National Bureau of Economics

Pascaline Dupas Stanford University; National Bureau of Economics

Victor Pouliquen J-PAL; Paris School of Economics

[1] Fizbein, Ariel, Norbert Schady, Francisco H. G. Ferreira, Margaret Grosh, Niall Keleher, Pedro Olinto, Emmanuel Skouas. 2009. Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank; Saavedra, Juan Esteban, and Sandra García. 2012. “Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs on Educational Outcomes in Developing Countries: A Meta-analysis.”

[2] For example, Blattman, C., Fiala, N., and Martinez, S. 2014. “Generating Skilled Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Experimental Evidence from Uganda.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 129 (2): 697-752; Cunha, J. M., De Giorgi, G., and Jayachandran, S., 2011. “The Price Effects of Cash Versus In-Kind Transfers.” NBER Working Paper No. w17456; Haushofer, J. and Shapiro, J., 2013. Household response to income changes: Evidence from an unconditional cash transfer program in Kenya. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.